What I’ve Learned from Osamu Dazai’s “No Longer Human”

Either stay true to yourself or die trying.

“Mine has been a life of much shame. I can’t even guess myself what it must be to live the life of a human being.”

— Oba Yozo

Ningen Shikkaku, known internationally as No Longer Human, is a 1948 novel by the Japanese author Osamu Dazai. The novel has been critically acclaimed and widely considered to be Dazai’s masterpiece. Until today, it’s still the 2nd all-time best-selling novel in Japan, right behind Natsume Soseki’s Kokoro.

I only read the book last year, and I found it astonishing, to say the least. It’s the kind of book that peels into the deepest layer of your psyche, and forces you to confront the side of yourself you don’t want to see. It was uncomfortable, but that’s how all meaningful transformations happen.

In this article, I’m going to share with you what I’ve learned from No Longer Human. Before we go into it, though, let’s learn about the book itself.

What is No Longer Human about?

No Longer Human tells the tale of Oba Yozo, a miserable man who considers himself a faulty human being. His story is told mostly in the first-person perspective, with a personal-journal storytelling style (hence the book’s subtitle, Confessions of a Faulty Human Being).

Throughout the story, Yozo mostly uses the reflective pronoun “jibun,” instead of the more casual “ore” or “boku” —making the narrative somewhat more thought-provoking for the readers. It’s as if we’re invited to Yozo’s mind and think along with him, pondering the same thoughts he does.

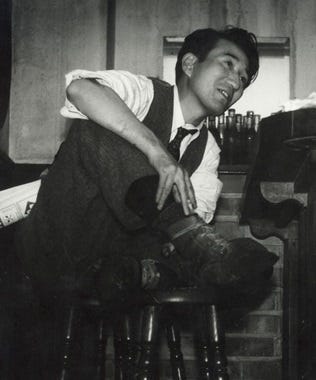

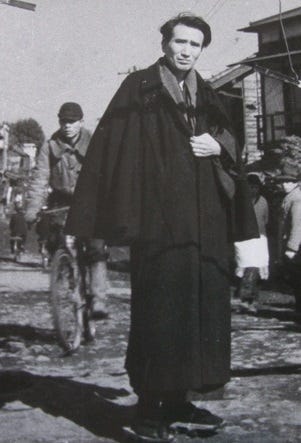

Many believed Yozo to be an avatar of Dazai himself, and No Longer Human to be Dazai’s will; seeing the myriad parallels between the two. Eventually, Dazai even took his own life after the book’s last chapter was published, mirroring Yozo’s descent into despair.

No Longer Human is structured into three chapters, each one a memorandum of Yozo’s life. Here’s a (very) short summary:

Book 1: Details the earlier parts of Yozo’s life. Since childhood, he has always felt misunderstood and alienated, which led him to adopt a clownish personality, hiding his pain behind a facade of buffoonery. He was sexually abused by his family servants but didn’t report it.

Book 2: As Yozo grew up, he began drinking, smoking, and sleeping with prostitutes. At one point, he had an affair with a married woman and the two of them attempted double suicide. However, only the woman died. Yozo survives and is consequently overcome by shame and guilt.

Book 3, Part 1: Yozo is expelled from university, and comes under the care of a family friend. He persists with his destructive drinking habits, finding inspiration in the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Later, Yozo enters a relationship with a woman named Yoshiko.

Book 3, Part 2: Yozo gets addicted to morphine. Meanwhile, his wife Yoshiko is sexually assaulted, and instead of seeking justice, Yozo blames her for being a victim. Afterward, Yozo fell into despair and was consequently put in a mental institution, where he eventually died.

According to translator Donald Keene, the more literal translation of Ningen Shikkaku is Disqualified from Being Human. This more faithful alternative highly suits the book, seeing how Yozo gradually falls into depravity as the story progresses — until he finally loses his humanity (or is “disqualified” from it) by the end of Book 3, Part 2.

Surprisingly enough, this fall-into-ruin story didn’t leave me feeling depressed — instead, it helped me learn an important lesson.

Learning from No Longer Human

As you’ve seen, No Longer Human is a dark and dismal story. This is a well-established trope, in Japanese stories especially. Japan has a lot of authors (like today’s Haruki Murakami, for example) whose works revolve around heavy themes like depression, suicide, and misanthropy.

I don’t know if this is a universal theme in Japanese society, or if it’s just the individuals themselves, but many Japanese authors are really good at writing stories with a despondent undertone. A comparable Western counterpart would be someone like Franz Kafka, known for his novella, Metamorphosis.

In my other writings, I’ve often stated that tragedy is my favorite genre, and the reason for that is something called catharsis or “emotional purging.”

Reading tragic stories and relating to their characters can help us “suffer without suffering,” thereby ridding our minds of negative emotions like fear, sorrow, and despair. This is also what I felt with No Longer Human.

As I make my way through the book, I find parallels between Yozo’s life and mine. For instance, much like Yozo with his “clown mask,” I wear my own “poker face mask.” That is, I almost never smile, frown, or show any emotions whatsoever. This is a behavior I’ve learned as a child, to protect myself.

I grew up in an environment where showing any sort of emotions — joy, sorrow, anger — is a risky gamble that will compromise my well-being. Over time, I instinctively learned to “man up” and bury all shreds of emotionality. This behavior is then imprinted permanently into my psyche.

As I grew up, I realized this behavior was unhealthy, and I’ve since moved to a new environment where I’m allowed to take off my mask. The thing is, I’ve been wearing this mask ever since I can remember, and now it’s permanently attached to my face. What is “mask” and what is “face” are no longer distinguishable. This is the kind of person my past had made me into.

I didn’t know any other way to live. Like Yozo, since a very early age, I was disqualified from being human.

What most people don’t understand is that nobody chooses to be this way. We don’t choose the family, culture, or environment we’re born into, and yet, our elementary years play the largest part in shaping who we’ll become in the future. While we all have a capacity to grow and make our own decisions, in more ways than one, our paths have been chosen for us since birth.

Our fate, albeit not all of it, has been carved even before we were born.

Unlike Yozo, I’ve never seriously considered or attempted suicide, but I feel like I understand where he’s coming from. Whilst some people might feel pity, nausea, or anguish when reading No Longer Human, I simply felt a sense of kinship with Yozo, and by extension, with Dazai himself.

I may have only lived for 25 years, but I live in the 21st century, where it’s never been easier to retrieve the thoughts and experiences of others across history — particularly those wiser and more knowledgeable than me.

By delving into the thoughts of Oba Yozo and Osamu Dazai, I’ve learned that we can only access our humanity through our flaws.

All my life I’ve been told that emotions make me weak, but they also make me human. Obvious as it is, no one ever taught that to my childhood self. All I ever knew was to be tough (or at least look like it).

After I closed No Longer Human’s last page, I made a decision: I’ll spend the rest of my life piecing together my humanity. I want to learn, as an adult, what I’m supposed to have learned since I was a child.

If I don’t do that, I might as well end up like Yozo.

After all, if I can’t be true to who I am, then I’d rather be disqualified from humanity.

Coda

“And now I had become a madman. Even if released, I would be forever branded on the forehand with the word “madman”, or perhaps, “reject.”

Disqualified as a human being.

I had now ceased utterly to be a human being.”

—Oba Yozo

In trying too hard to fit in, we’re prone to forget about ourselves.

We reconstruct our identity to seek the approval of others, while we’re not even sure if we’d approve of the person we’ll become.

In the end, nobody’s happy.

To me, Oba Yozo is a textbook example of Jean-Paul Sartre’s “bad faith.” He tried to fit himself into society’s mold, and in failing to do so, thinks himself a reject. He can’t understand other humans, so he concludes that he’s the one who isn’t human. From there, everything only goes downhill.

The bottom line is, either stay true to yourself or die trying. If you deny who you are, it’s only a matter of time before you’re no longer human.

This essay was originally published in History of Yesterday on 15 March 2022.